War Porn

Myanmar, Baudrillard, Ukraine, and Pornhub

Sometime in the past few years, I came across a post on Twitter of two young men standing in a clearing among tall grass, both wearing football jerseys. They also wear military-style plate carriers with ammunition pouches attached to the front. Like nearly all plate carriers, they have patches velcroed to them. The patches identify both men as members of the People’s Defence Force’s Cobra Column in Myanmar, fighters against the oppressive military junta that has ruled the country since the 2021 coup. But Thar Yair Naung on the right, whose account the picture was posted from, is also wearing another patch. Attached to a velcro panel on a pouch at the bottom of the plate carrier is a small patch featuring the black-and-orange logo of the website PornHub.

Seeing the PornHub logo being worn by a combatant in a modern war isn’t actually that surprising. Ukrainian soldiers have often worn Velcro patches with the logo or riffs on it since at least the beginning of the Russian invasion in 2022. Patches with the PornHub logo have been seen across numerous conflicts around the globe, worn by soldiers, militiamen, police officers, and other armed individuals.

What was surprising was that the patch had become so ubiquitous that it appeared in a conflict country with severe internet censorship and little access (that said, Yair Naung is quite active on Twitter and the anti-junta forces have been extremely savvy with their use of social media).

The ubiquity of these patches, cutting across continents, cultures, conflicts, and internet access, speaks to the increasingly globalized nature of military culture. Its styles and aesthetics are shared on social media, homogenizing outsiders’ perceptions of war. In our social media age, conflict has become globalized and flattened. Combatants can learn from the tactics and strategies of other ongoing conflicts by watching their peers engage in other wars on social media. These pornhub patches worn by fighters are signifiers of this globalized, social-media-savvy approach to armed conflict.

But why the Pornhub logo? The connection between warfare and pornography feels almost too obvious to dwell on in an age when social media platforms like X have become a constant onslaught of pornbots and graphic videos of death from Gaza to Ukraine.

In 2004, the French social theorist Jean Baudrillard coined the term “War Porn” in an essay of the same name. In the short essay, Baudrillard, looking at the American war in Iraq and the images of the prisoners being tortured and abused in Abu Ghraib prison, compares explicit images of war with the aesthetics and production values of modern pornography.

Both combat footage and pornography are a parody of the events they purport to capture, vulgar and spectacular. I am reminded of the scene in Michael Hastings’ posthumous novel The Last Magazine, where a fictional Hastings spends the first days of the 2003 Iraq War in his New York City apartment flipping between CNN coverage of the invasion and cable porn. In his memoir, he recounts the same experience: “On March 20, 2003, the war started. For the next forty-eight hours, I watched TV, nonstop it seemed, switching between live coverage of the invasion and Adult Videos on Demand, alone in my New York apartment, thinking, I want to be over there, I want to be in Iraq.”

Today, you can watch drone feeds and helmet cam footage on nearly any social media platform. Independent “creators” have sprung up to curate combat footage on social media pages with tens of thousands of followers (and back-up accounts for when they may be banned). The footage is often helmet-cam POV-style, shot by an anonymous fighter, raw but edited, filled with curse-laden commentary, and with gore often blurred to skirt social media rules.

The conflict with by far the largest number of Pornhub patches is the ongoing war in Ukraine. They are near ubiquitous — especially a riff on the logo that replaces the word “Pornhub” with “3CYHub.” 3CY is the acronym for the Ukrainian Armed Forces, with the Pornhub style patches first appearing in 2022. But the Pornhub logo patch being worn by Ukrainian troops dates back to at least 2021.

The reason for the popularity could simply be some good old-fashioned grunt humor, like Roman Legionnaires scratching penises into stone anywhere they went. Others have postulated that the patch is a kind of reference to how Ukrainians are “fucking Russians” on the battlefield. The war is also constantly being recorded in a way never seen before. The level of combat footage and compilations is astounding, most edited to show only the action of combat itself, showing domination of the enemy. These graphic videos are uploaded and passed around on social media in much the same way as porn, with a similar goal to titillate the viewer and create a fan.

Porn (not war porn) has also played a strange role in this conflict. In 2023, Wagner (the Russian mercenary group) took out advertisements on Pornhub in Russian with a voiceover saying, “Don’t whack off, go work for PMC Wagner,” as if promising the thrill of combat to be greater than an orgasm. Later, when North Korean troops were sent to fight in Ukraine, news reports asserted that they were ‘gorging themselves’ on internet pornography, which they had never had access to.

But again, this is just simply the latest manifestation of a timeless connection. In Greek mythology, Aphrodite (the goddess of love and desire) becomes the illicit lover of Ares (the god of war) after all. In his philosophical meditations on combat, J. Glenn Gray writes, “War offers us an opportunity to return to nature and to look upon every member of the opposite sex as a possible conquest, to be wooed or forced. For such a view, Ares and Aphrodite are kindred gods who need and understand each other. Both are under the control, however, of some larger evolutionary principle, usually called the struggle for existence or the will to live.” ( Gray’s book The Warriors is a must read).

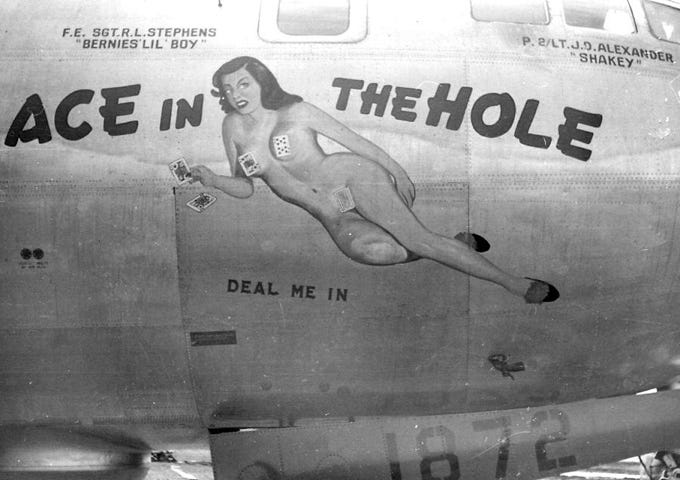

During WWII, pin-ups were painted on the noses of planes. Many of the ones we see now, whether on TV or on historical aircraft, are PG-13 versions. During the war, these pin-ups and the names were often much more pornographic, with names like “Ex-Virgin,” “Tender Tit Tillie,” and “The Sex Maniacs.” One US bomber pilot recalled after the war that German fighter pilots must have thought they “were being attacked by a wave of flying underwear catalogues.”

These giant four-engine machines that delivered death and destruction, adorned with women in erotic poses, personify the relationship between Aphrodite and Ares. J. Glenn Gray again, on the experience of combat, “Just as the bliss of erotic love is conditioned by its transiency, so life is sweet because of the threats of death that envelop it and, in the end swallow it up.”

Karl Marlantes, a Vietnam veteran and author, wrote it more simply, “combat is like unsafe sex in that it’s a major thrill with possible horrible consequences.” Which fits nicely with Baudrillard’s own analogy in The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, his essay on the Gulf War as a non-event, a simulacra of war, writing this non-event is “the bellicose equivalent of safe sex: make war like love with a condom!”

It seems incredibly fitting for Baudrillard that the sign would evolve from pin-ups on the side of planes to a simple Pornhub logo on a plate carrier.

Till next time,

C.W.M.

* * *