Before we get into this week’s post, I have something to plug. Last week I was a guest on the podcast Apocolypse Duds. In the episode, the hosts and I talk about post-WWII surplus and how I got started down this path of research and collecting and rejecting “grail” culture. Give it a listen. Meanwhile, here —— I am diving into an obvious connection but had yet to spend any real time researching or writing about. Blue jeans and military surplus are both significant pillars of casual American style, and their acceptance and rise to popularity are intrinsically linked together.

* * *

The connection between Military surplus and denim has been there since the beginning. With canvas sneakers, T-shirts, and sweatshirts, jeans and military surplus are the blank canvases of American style. Adopted by countless subcultures, from bikers and hot rodders to hippies and punks. Their uniformity and utilitarianism are the perfect vessels for any group’s identity. Their lack of intrinsic fashion allows them to become anyone’s fashion.

Surplus uniforms, similar to denim, has its roots in American workwear. In the postwar period, industrial and rural workers wore military clothing as workwear. Available in stupendous quantities, well-made for rugged wear, and cheaper than commercially made workwear, the military surplus was an obvious choice for workers. Right after the war, the Dean Brothers opened up “Dean Government Surplus.” The brothers were able to buy khaki trousers from the government for $2, a quarter of what new trousers retailed for in 1946. "People would come in and buy a dozen pairs of pants at a time," said one of the brothers in a Smithsonian Magazine piece on war surplus. The son of an Army Navy Store owner in Orange County, California reflected decades later, “the store had camping gear, canvas, clothing, work shoes and much much more… Men from all over would come at regular intervals to buy their ‘gear.’”

This trend is demonstrated by a striking dairy farmer captured by a Life Magazine photographer wearing an M-1943 field jacket with his overalls and wool work cap and another image of an auto-worker walking past the open casket of Henry Ford, “still in factory clothes,” also wears an M-1943 field jacket. This mix of workwear and uniforms was further canonized in the 1954 film On the Waterfront. A Newsweek article from 1965 called surplus stores “that old friend of the workingmen, stevedores, and sportsmen.” While not as poetic as “beating swords into plowshares,” the uniforms of WWII played an integral role in outfitting the workers.

Surplus stores quickly began to stock more traditional workwear among the military gear. Jeans and other work pants, along with work boots, became part of the Army-Navy Store inventory. Writing of the importance of military surplus in American Men’s style in his essay “Up from the Bottom: Roots of American Style,” G. Bruce Boyer recounts:

“We all bought our jeans there [the Army Navy Store], either Levis, Wrangler, or Lee, the only three brands sold in the 1950s. And the accompanying denim ranch jackets, unlined in summer, flannel lined for winter. Some guys would cut the sleeves off and wear the jackets as vests. Before the age of manufactured-distressing, we soaked our denim in buckets of water to get some of the indigo dye – which stained the hands -- and stiffness out. I still have the smell of new jeans in my memory.”

By the 1960s, nearly any reference to surplus stores in the media mentioned jeans or dungarees. In 1965 the Chicago Tribune wrote, “it may not be fashion, but it’s a current passion among the teen-agers to borrow from the boys in blue [sailors].” The New York Times noted a similar trend of college students heading to the surplus store. At the Army-Navy Surplus store on 42nd St. “socialites and college girls” crowded out the male surplus store customer in their fashionable search. The “fashion customers” had started shopping at the surplus store a few years prior, according to the owner, when “girls took to men’s dungarees.” The salesmen of the surplus store worked to translate men’s military sizing to women’s. The article features two college students, one looking for a peacoat and the other for an Army shirt. Today, while surplus stores are more scarce, they will still stock jeans and work boots. Students were attracted to surplus and denim for various reasons.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, the collegiate style had become increasingly casual. Women students' fashions of the 1950s would be described as “sloppy” and often included dungarees or Military Surplus. This photo from Elmira College in 1945 shows a group of students all wearing “Discarded Army, Navy, and Marine Corps uniforms” as well as two of them in cuffed dungarees.

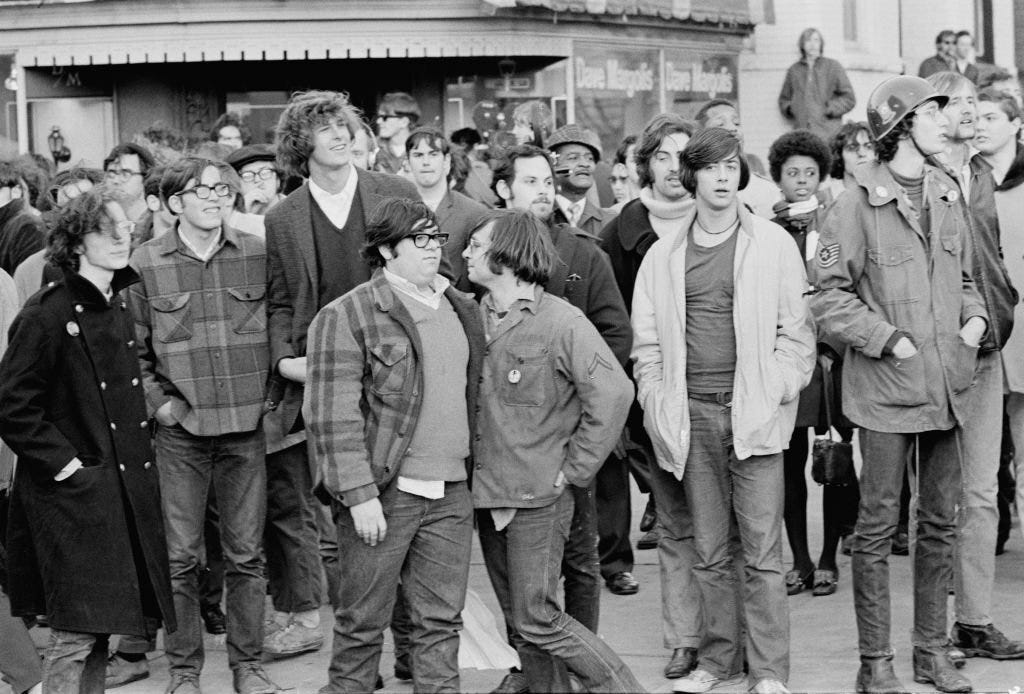

A few years later, in the late 1960s, with counter-culture movements and anti-war movements sweeping the country, denim and surplus styles blossomed among college students. Denim and surplus took on a political tint. Blue jeans and olive drab became the colors of non-conformity and resistance against the dominant American culture of conformity, consumerism, and support for the war in Vietnam. As one Army Navy store manager in Boston said in 1970, “the kids tell me they’re boycotting fashion and rebelling against the system. I believe them.”

Along with the Army-Navy store surplus, denim would become the defining style of the late 1960s. The expansion of jeans surplus into collegiate fashions was part of the general trend toward more rugged and casual clothing for students. But, unique to the late 1960s, jeans and surplus also figured prominently in social and political movements of the era. They were more than just rugged, hard-wearing, and cheap clothes for students. “If jeans or army surplus were just sturdy and cheap, would they enjoy the prestige they do? Beyond their obvious material advantages, their uniformity speaks to a generation that finds its identity en masse (the Peasant, the worker, the soldier, the primitive horde – whatever mass preys upon urban civilization, suffers at its hand or renounces it, whatever mass lives outside it.),” wrote a professor at Stony Brook University in 1972. While not in uniform, military surplus and denim as a uniform by young people signaled their opposition to the status quo, or as the professor wrote, “outside of it [society].” The use of uniforms as a tool against uniformity is, of course, ironic, but more importantly, it is attempting to remove clothing from fashion and by extension, American consumer culture.

The garments in question, blue jeans and olive green fatigues, and field jackets were not designed as fashion but as utilitarian garments which may make up the raw material needed for an individual style. Made outside the fashion system, they can be used for true self-expression and not what is fashionable. Interviewed by the Boston Globe, one female student said in 1970 fashion “is the epitome of competition. It is the basis of a materialistic society.” Further along in the piece, a Radcliffe student comments, “the great counter-culture movement has instigated a breakdown in traditional dress. There has been a great change in values. Fashion designers have lost their control.” The author continues, “The young who are boycotting fashion are examining the whole concept of American advertising and the Madison Avenue myth, which chips away at the subconscious by hammering home the idea that trappings, like fashion, are a mark of excellence.” At the heart of the denim and surplus style was rejecting the dominant American culture.

Jeans had been strongly associated with the fiercely independent rebels and those on the edge of society for decades through movies like Rebel Without a Cause and The Wild One. In the 1960s and 70s, army surplus began to be as well, first, like jeans, through genuine popularity and then through cultural products. Movies like Serpico and Taxi Driver made military surplus instantly recognizable as symbols of disaffection, opposition to the status quo, and general outsider status.

It is a mistake to think that there was no style to the uniform. While the mix of surplus and denim may have been made of uniforms, it did not make for uniformity. The skeptical Stony Brook professor aptly wrote, “nestling in these among the sameness you always find are these little personal touches, always just a little something to adapt the uniform to a private sense of style.” by opting out of dominant fashions and trends, students believed that the true self could come out. What the professor calls “private” style could easily be interpreted as “personal style.” Jeans and military surplus were the raw material used to create a personal style, blank canvases (sometimes literally) that young people could use to express themselves and form identities.

Till next time,

C.W.M.

* * *