Vol. 02 No. 03

Welcome back to Combat Threads. This week I am going to pick up where I left off on Desert Storm T-shirts with a slight tweak. I am actually going back and putting the whole essay here in two parts instead of in an abridged serialized format. So, for old subscribers, there is going to be some old stuff you read already, for those new you are going to get the whole story here. Last week I was a guest on the Heddels Blowout podcast talking all things problematic camouflage patterns. Give it a listen and I expect I will write a post on the topic sometime soon. Let’s get back into the world of Desert Storm T-shirts.

***

The Gulf War saw an unprecedented outpouring of pro-American sentiment in the country. Observers compared the feelings in the country to that of WWII to quote a T-shirt, “A Nation United.” While the patriotic fervor was compared to that of the 1940s, this new patriotism manifested in the 90s tradition of graphic T-shirts. The graphics of the T-shirts ranged from relatively benign maps of Iraq and American flags to crude racist cartoons of Saddam Hussein or generic ‘Arabs.’ The T-shirts produced around the Gulf War were part of the proliferation of screen printing, cheaper goods, and mass consumption. The printed graphic T-shirt is one of the most ubiquitous pieces of clothing throughout the world. Since the 1970s, graphic T-shirts have become increasingly common and a canvas on which a literal message and texts are displayed. T-shirts, “unlike most clothes which mumble and stammer their messages, the t-shirt "talks" directly to its audience.” The merchandise produced around the Gulf War was part of the proliferation of screen printing, cheaper goods, and mass consumption that led to T-shirts and sweatshirts becoming objects of souvenirs for everything from band tours to war.

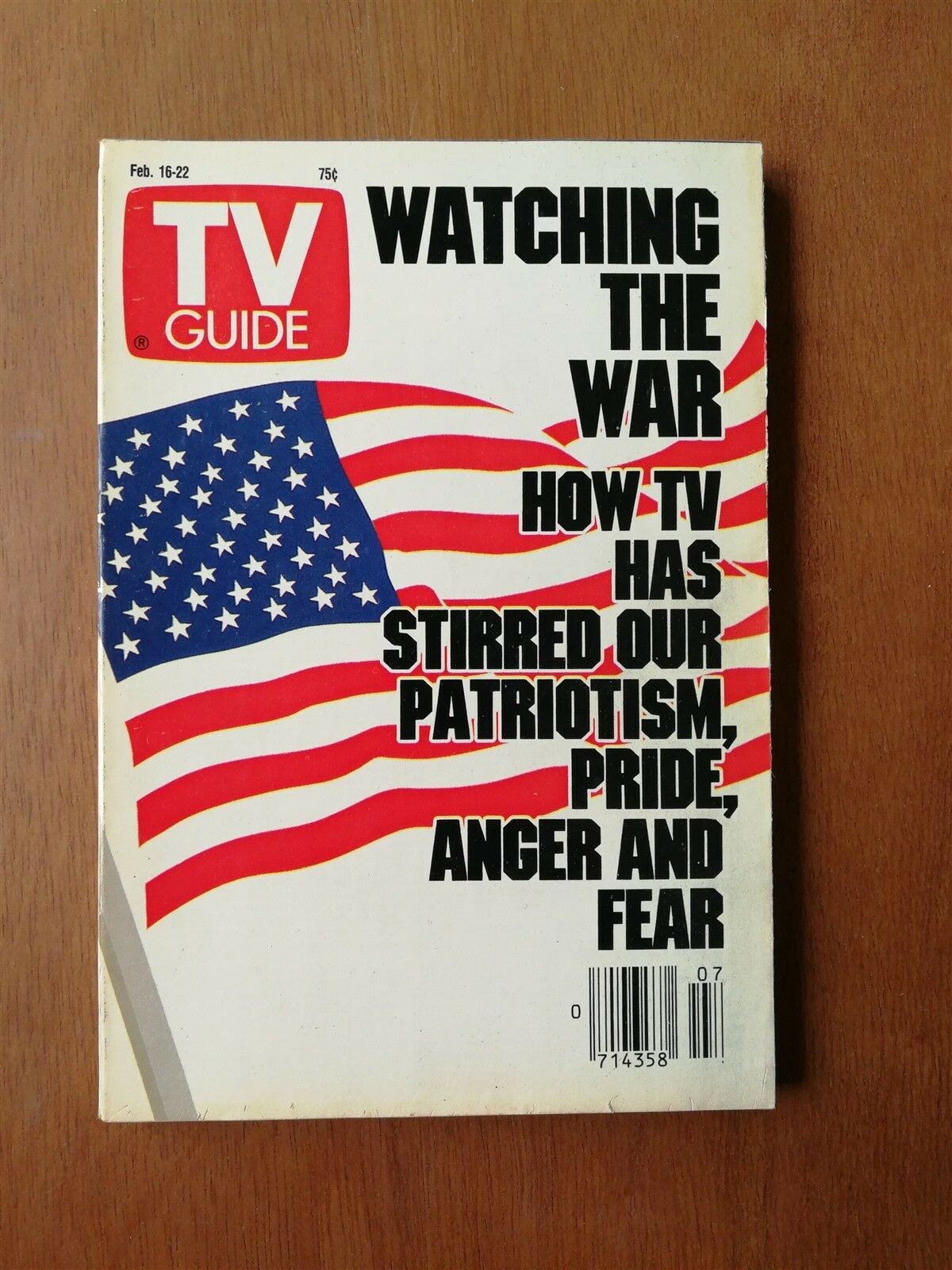

During the month-long war, the conflict was broadcast around the clock. CNN’s rating went up 271 percent. The eight-hour time difference to the East Coast allowed television channels to carry footage of the war in prime time. The military press officers and the new electronic warfare apparatus gave such a large amount of data (e.g., the ability to broadcast live 24 hours a day) that the journalists’ task of selection and reflection became impossible. The coverage of the war became devoid of critical questioning and just a constant never-ending collection of visual data (a map of Iraq, a Scud missile, a camouflage pattern, a blown-up tank, black smoke of an oil field, grainy footage of a bomb strike, gas masks, etc.). The war was presented to the US public purely through entertainment, “a tourist attraction, a picture on a postcard: the army had finally fulfilled its promise. Total War had been transformed to Total Entertainment.”

Signs and Symbols

In Culture and Consumption, Grant McCracken argues that the fashion object (in this case, the Gulf War T-shirt) acquires meaning in two steps. With T-shirts of the Gulf War, the meaning is first drawn from the constant news and media coverage delivering images, words, and video of the war and its lead-up. These are then transferred onto T-shirts by what McCracken refers to as “agents of meaning transfer,” in this case, graphic designers and screen printers. This meaning (pro-war patriotism) is bound up and communicated through the T-shirt but, more specifically, the signs and symbols that comprise the design of the T-shirt. This can be literal as in depictions of warplanes or “Desert Storm,” or connected through culture like the American Flag or a Bald Eagle.

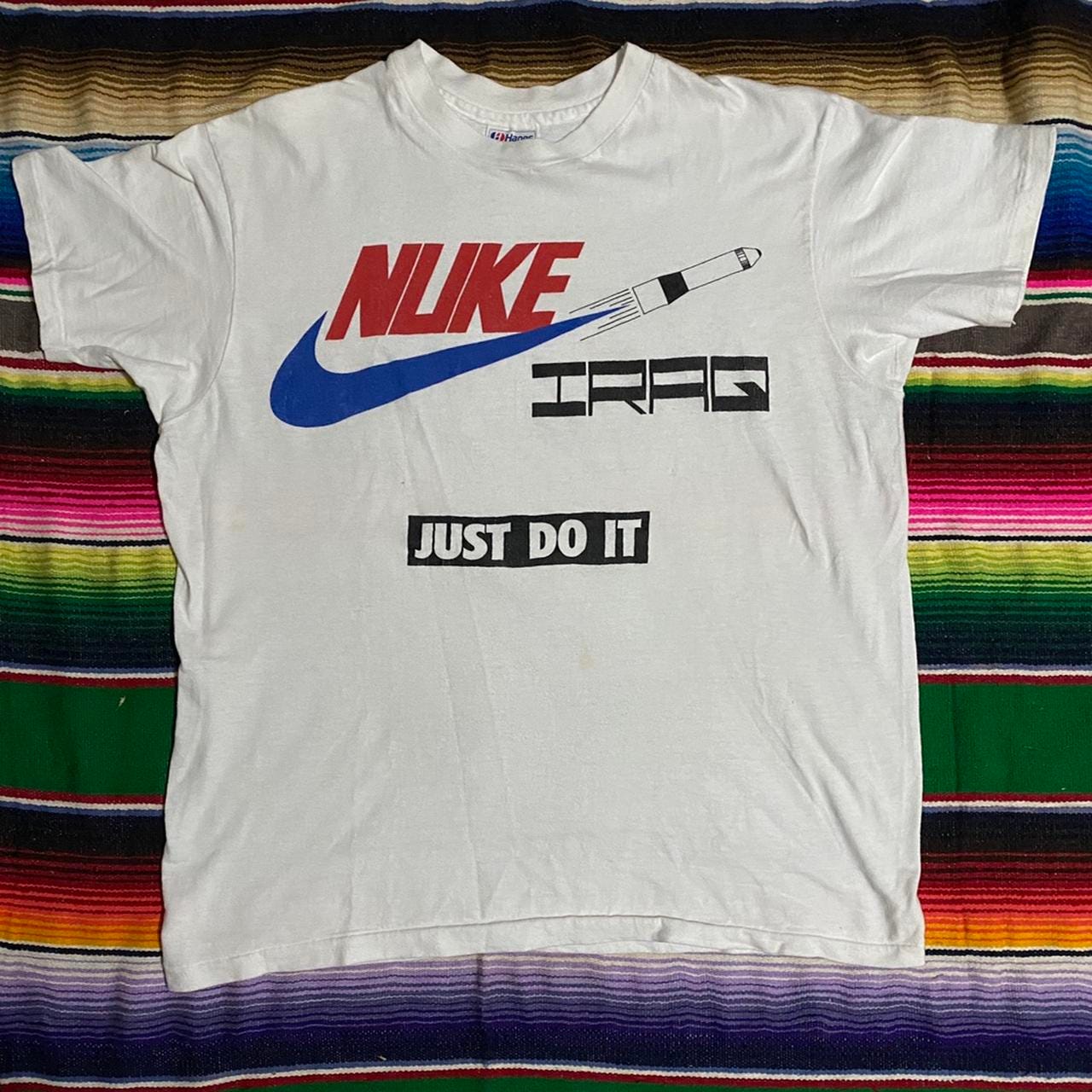

While Desert Storm creates its own language of signs depicted on T-shirts, the war is also recontextualized through the language of graphic T-shirts. Joke, souvenir, and advertisement T-shirts are all reworked and reprocessed within the context of the War. Some T-shirts incorporate popular cartoon characters, mimic concert tours and Spring Break souvenir shirts, and reimagine brand names and advertisements (‘Just Nuke Iraq,’ ‘I’d Fly 10,000 Miles to Smoke a Camel’). All images of the T-shirts are “second-hand,” (be it the Nike swoosh or Saddam Hussein cartoon) becoming hyperreal. These signs create a shared code of Gulf War T-shirts.

The T-shirts produced during the Gulf War operate within a postmodern system in which images (the American flag, a missile, a warplane) removed from their original context become hyperreality (“signs about signs taken to be objective or universal opinion or truth”) that can be endlessly reproduced. The reality of the T-shirt refers to that which is created by the image itself and accepted. As the images are produced and reproduced, they become a social reality. “The postmodern shirt is something of an open text, a functional carrier of signs and signs about signs that variously signify social relations, the self or identity of a wearer, and other t-shirts. The shirt floats with other simulacra in the sense that few social constraints govern its content or occasion.” These T-shirts are no longer articles of clothing worn for durability, comfort, or fit, but rather consumed and worn (or not) purely as an expression of political alignment and self-representation in everyday life.

T-Shirts of the Gulf War

Media coverage of the T-shirt trend began in the Fall of 1990, a few months after the initial Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait. On October 15, 1990, the Virginian Pilot published “Saddam To a `T' Desert Shield Fashions Latest In,” referring to the US military operation name to build up to the war. Various T-shirt styles appear with interviews with local Virginia screen printers and vendors. Simple shirts with ‘Desert Shield’ printed on them, along with a design of a robe-clad cartoon riding a camel with rifle crosshairs over him with the phrase “I'd fly 10,000 miles to smoke a camel” printed on it. This was a riff on the longstanding Camel cigarette advertisement slogan “I’d walk a mile for a Camel.” This kind of appropriation of commercial advertising for humor and double entendre (In this case, “smoke” means to kill instead of inhaling) is foundational to slogan T-shirts. The Gulf War provides more examples of this, with one egregious example being “Just Nuke Iraq Just Do it!” with the graphic of the Nike swoosh as the trail of a rocket.

Throughout the literature, there is an acknowledgment of a patriotic fashion craze running through society. It shows itself in simple T-shirts and, as a broader fashion trend. Celebrities were photographed in Ralph Lauren flag sweaters, and sales of stars and stripes silk scarfs were "phenomenal.” Department stores like Macy’s and Neman Marcus added “America Shops” for patriotic wares, and stocks of flag lapel pins ran dry. In a comparison made across nearly all facets of the war, the appetite for patriotic clothing was reminiscent of WWII, “such flag-waving clothing has not been so popular since the 1940s,” as one newspaper put it.

This outpouring of patriotism through commerce reflects the public attitude towards the war in the Gulf and the relationship between outward displays of patriotism and fashion. Unlike in the 1940s, wearing the flag and, by extension, other overly patriotic messages on clothing was commonly acceptable. This is partly due to the 1960s counterculture wearing the American flag as clothing, notably Abbie Hoffman, who was arrested for wearing an American Flag shirt on charges of breaking the flag code. In the 1990s, many states still had laws on the books prohibiting the wearing of the flag, though it was rarely enforced. The culture around the wearing of the flag has drastically changed from protest to patriotic conformity. One American Flags seller quoted in The Baltimore Sun said, "not since World War II has this country seen this sort of thing."

Many of the Gulf War T-shirts use the operational names for the different phases of the war (“Desert Shield '' and “Desert Storm”) to ground the meaning and message of the design in the war with little other context clues. As designs become more complicated, they become more rooted in the signs of the war. Some shirts feature all the flags of the 39 coalition countries in a fashion akin to a TV news graphic. Others are reminiscent of Newspaper headlines on the front page, map graphics showing troop movements on a map of Iraq, yellow ribbons, the UN Flag, and even printed graphics of the American desert camouflage pattern. These examples are all referential to other media, copies of copies creating the context for their consumption.

This kind of contextualization of the T-shirts is also seen in the use of specific military equipment in graphics, most notably Scud missile launchers. Scud missiles became an important part of the news coverage of the Gulf War as Hussein launched them at Israel, and Saudi Arabia and the threat of poisonous gas-laden Scud missiles led to images of soldiers and civilians in the region donning gas masks against possible attacks. Rockets became one of the most prominent graphics used on shirts in both humorous and pun-filled shirts. The flat, dull sound of “Scud” made it easy to lampoon in shirts like “Don’t be a Scud be a Patriot”. This also had a dual meaning. While the Iraqi missiles were called Scuds, the American anti-missile system (autonomously launched missiles designed to shoot down Scuds) was named “Patriot.” Designs would feature a Scud missile broken in half, intercepted by another missile with “patriot” written on its side, with the slogan “Scud Busters''. The phrase “Scud Buster” was used throughout the media at the time, including in the headline of a Washington Post profile of a US Patriot missile launcher team in Saudi Arabia published less than a week into the air war. Working backward from “busters'' some T-shirt designs featured the slogan “Who Ya Gonna Call?” taken from the tagline of the 1984 hit film “Ghostbusters.” The cross-contamination of hyper-specific references and broad pop culture is an important element of slogan T-shirt designs. “The t-shirt designer is, above all, a recycler…giving new lease of life to second-hand images, offering new texts and contexts for the texts of advertising.”

A large number of T-shirts engaged with broader popular culture (the war, as a media event, is itself popular culture) and were aimed at being humorous. The slogan T-shirt is often associated with humor, double entendre, as seen in any tourist shop stall along in shopping districts around the world like Canal St. in New York. T-shirts made to commemorate a war are no exception. While some of the humor is derived purely from association (“Who Ya Gonna Call?”), more often they mocked Saddam Hussein as a caricature and played into racial and religious stereotypes in openly racist and hostile designs. These designs are, of course, designed to elicit a response preferably one of humor, but they also deploy humor in other ways. “employing humor within these garments also function as a popularizing and protective device. People often dismiss humor as unimportant,” writes Neal Lynn on the subject of Religious intolerance in 21st Century T-shirts. He continues:

But studies of humor also argue that “laughter produces an atmosphere of fellowship among participants in the group and simultaneously, a united front against outsiders”. As a result, the dominance of “nonIslamic America” (or as one T-shirt proclaims “The U.S.A. is not a ‘Muslim Country’”) remains intact and upheld, while the butt of the joke—Islam—resides in a position of inferiority and continued disparagement. In this way, humor combined with existing stereotypes helps mute the intolerance of this imagery and construct these T-shirts as acceptable apparel.

The Gulf War T-shirts operate in much the same way. We have already looked at the “I’d Fly” T-shirts as an example of the ugly humor of the T-shirts. Also, using a camel, another design with the slogan “Iraqi Mobile Scud Missile Launcher” depicts a camel, its head towards the sky, a missile sticking out of it. Behind, a man in robes holds a large mallet over his head, preparing to strike the camel’s testicles which are enlarged and placed on a tree platform or tree stump. This crude vulgar T-shirt even got the attention of President George H.W. Bush. At a rally in North Carolina in early February 1991, many of the crowd held up T-shirts. The President spots a little girl with a shirt, and says “What’s that T-shirt here?” The crowd applauds, and a woman pushes a little girl up to the President with a T-shirt with the “Iraqi Mobile Scud Missile Launcher” graphic. He “faked shock” and tucked it under his arm. This shows just how widely popular and known such slogan T-shirts were.

Other similar designs include graphics of Hussein as a caricature with a missile striking his posterior and him being hung with the slogan “it's not over till the fat man swings”. A widely seen design was Hussein depicted as a giant spider, legs spread over a map of Iraq and Kuwait with “Iraqnophobia” printed on it. This was both a play on arachnophobia, the fear of spiders, and a blockbuster horror comedy film of the same name which came out in the summer of 1990 only a few weeks before Iraq invaded Kuwait. At the core of this genre of T-shirts are the contradictions, both vilifying Hussein as a Hitler-like evil figure while also making him the butt of jokes, of warning of the Iraqi military as dangerous while also hopelessly backward. It all serves the purpose of trivializing the war and its destruction.

Specific references to brands (‘just Nuke Iraq’) and visuals of popular culture were inseparable from Gulf War T-shirt designs. One of the oddest pairings in this regard was the widespread use of Bart Simpson on many shirts. The Simpsons aired in December 1989, and by Spring 1990, The New York Times was writing about “Bartmania” sweeping the nation with one company “selling several hundred thousand T-shirts a week.” T-shirts with Bart Simpson on them became a global phenomenon with both legally licensed and illegal bootleg shirts selling everywhere and putting Bart anywhere. Writing in 2021 about the phenomenon, Molly Young at SSENSE captures the spirit of these bootleg T-shirts:

Many of them were riffs on the Bart Simpson character, using his signature traits—lack of respect for authority, allegiance to skateboarding, mastery of pranks—as a symbolic prompt for bizarre or subversive or foul or funny commentary in 100% cotton tee form. The point was not to trick people into buying a fake Bart shirt; it was to offer a fake Bart shirt that was incontestably fake and obviously superior to the legally-sanctioned options.

When the Gulf War came, it was only natural that Bart would be shipped overseas. Some of the Bart T-shirts were simple designs, depicting him urinating on a map of Iraq and a “here’s to you Iraqi dudes!” in a speech bubble. Other more complicated designs feature Bart in full camouflage choking Saddam Hussein. These shirts exemplify how Gulf War T-shirts rose to a “Bartmania” level of popularity. Many news reports of the Gulf War T-shirt trend mention the previous Bart Simpson T-shirts as a reference point, saying, “The hottest selling T-shirts hit fads at their peak, like Bart Simpson shirts.” But far from a fad, the Bart designs are the Gulf War T-shirts with the most longevity, with companies now making reproductions of the 1991 designs and reference to the designs appearing regularly on social media.

Next time, more on the media reaction to the popularity of these designs in 1991.

Till next time,

C.W.M.

* * *